In a course I teach on the social contexts of schooling, elementary teacher candidates learn about the potential impact of racisms, sexism, homophobia, ableism, and social class on teachers and students. The critical pedagogies we work with over the course of the semester involve deconstructing curriculum and popular cultural texts as well as our own assumptions. Media literacy becomes a key lens for teachers to examine their identities as well as those of the students in their classrooms.

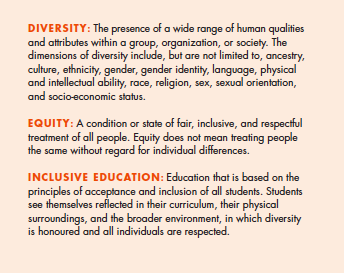

The course focuses on the concepts of identity (Stern, 2008) and representation and their relation to diversity, equity, and inclusive education (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2009). Few people realize we learn more about people different from ourselves from popular media cultures than from all other sources of education. Therefore, teachers need to be able to critically read not only curriculum texts, but also mass media representations of difference. In addition to learning critical skills, they also gain understandings of what it means to children and youth personally and academically to never see themselves or their perspectives represented.

However, reading media messages is only one aspect of critical media literacy. Teacher candidates and their students also need to become digital authors who understand “the power of authorship” (Hobbs & Moore, 20013, pg. 8) in our participatory culture (Jenkins et al., 2006). The focus of literacy shifts “from one of individual expression to community involvement” (pg. 7). We have certainly experienced this shift in this course on digital authorship.

EXPANDING THE CONCEPT OF AUDIENCE

Being a member of this class on digital authorship with Renee Hobbs has meant having to access, create, and share understandings and knowledge collaboratively using digital tools. My personal experiences have prompted me to rethink many of my practices as a teacher educator. For example, writing our assignments as public blogs is very different than writing a traditional paper in a number of ways. The latter is generally written for an audience of one – the teacher. When we post online in this course on our websites and share within our group and more widely via Twitter, our message is potentially available to anyone with an Internet connection.

Having a broad audience can motivate one to produce better quality texts. It can also motivate creativity knowing more people might read it. Digital texts have the added advantage of enhancing the message through the use of sound, images, and multimedia rather than print alone. Access to these modes of meaning making open up communicative possibilities for students, including those who struggle with traditional print-based literacy. Of course, students also need to learn how to be responsible to themselves and potential audiences (Lange, 2014). Awareness of message and how it could be received by various audiences has become an important literacy. Even though we can’t know who will read our images, videos, and texts, it is important to provide students with opportunities to think critically about message and audience.

EXPANDING CONCEPTS OF CREATIVITY, COLLABORATION & SHARING

To engage the critical lenses introduced in my course on the social contexts of education this semester, teacher candidates were asked to deconstruct a curriculum resource. They completed critical readings of movies, storybooks, curriculum documents, and other texts used by elementary teachers in the classroom. In the past I have always had students write these as a resource to share with colleagues. A few years ago they brought hard copies to class to share around to everyone, and more recently these teacher resources were posted and shared on the class Wiki.

This semester our notion of audience has expended beyond our class as students were invited to create their resources as digital texts. Students were encouraged to share their texts on Twitter. Again, sharing curriculum resources with broader audiences may instill a feeling of pride and accomplishment. Perhaps more importantly, student teachers are spreading the critical work they are doing in the class to challenge stereotypes and promote inclusive educational practices with teachers who may not have the time or the inclination to develop such lessons on their own. This illustrates the potential power of digital authorship in participatory culture, as teachers design texts that can be widely circulated.

Katie and Ainley collaborated on a critical analysis of an Ontario Ministry of Education literacy resource document targeting boys. Using a gendered lens, they argue the recommended strategies should be used with ALL students. They were comfortable sharing this on Twitter:

Nana’s teacher resource describes how to engage anti-racist pedagogies with elementary children using Dr. Seuss’ The Sneetches:

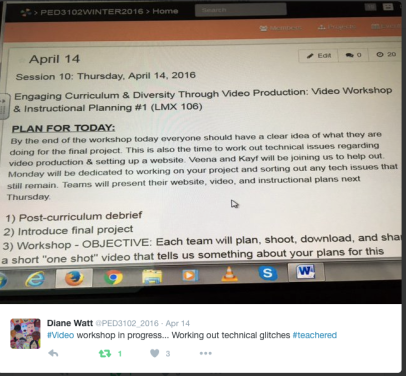

VIDEO PRODUCTION PROJECT WITH TEACHER CANDIDATES

For my final paper I will write about the video production project I am carrying out with teacher candidates in the schooling and society course. I wonder how video can be used in elementary classrooms across the curriculum to promote educational spaces where all identities and perspectives are welcomed; where all children feel a strong sense of belonging. What can digital video as multimodal text do? How is it different from other forms of representation for both creator and audience?

(From: Ontario Ministry of Education, 2009)

Hobbs and Moore (2013) assert it is essential that elementary teachers focus on helping students develop self-expression and communication skills (pg. 10). Video production provides an opportunity for even young children to represent their identities and perspectives in a fun and engaging way, while also meeting cross-curricular expectations in subject areas such as Language Arts, Social Studies, and the Arts. Research demonstrates that including media production in the classroom can promote civic engagement (Hobbs et al., 2013) as students gain experience both decoding and creating their own messages. For these reasons, teacher candidates were asked to design instructional plans that engage diversity and curriculum expectations through video production, and the preliminary results are truly inspiring.

This is the Storify text I curated to provide teacher candidates with resource materials for this assignment:

https://storify.com/DianeWatt/final-project-engaging-curriculum-diversity-throug

Connecting elementary students’ media worlds to the classroom and to their lives is a messy proposition (Hobbs & Moore, 2013). There are challenges, risks, and benefits associated with video production in schools. From what I have seen so far, the curricula and videos designed by teacher candidates in my course demonstrate it is not only possible to have students produce media that engages diverse identities and curriculum in the elementary classroom, it is well worth the effort!

Introduction to video instructional plan, produced by teacher candidates: Riley Hoban, Lianna Krantzberg, Maya Tomczak & Caitlin Starkey

Participating in this open-platform online course in digital authorship has provided us with critical insights into the latest research in the field. Just as significantly, we have gained valuable hands-on experience working collaboratively with a multitude of digital tools. In my experience, this has been a powerful pedagogy, which I am now passing on to my own students in much more meaningful ways.

REFERENCES

Hobbs, R., & Moore, D. (2013). Discovering media literacy: Digital media and popular culture in elementary school. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin/Sage.

Hobbs, R., Donnelly, K., Friesem, J., & Moen, M. (2013). Learning to engage: how positive attitudes about the news, media litearacy, and video production contribute to adolescent civic engagement. Educational Media International, 50(4), 231-246.

Jenkins, H., Puroshotma, R., Clinton, K., Weigel, M., & Robison, A. (2005). Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Lange, P. (2014). Kids on YouTube: Technical identities and digital litearcies. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Ontario Ministry of Education (2009). Realizing the promise of diversity: Ontario’s equity and inclusive education strategy.

Stern, S. (2008). Producing sites, exploring identities: Youth online authorship. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, Identity and Digital Media. John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Initiative.